Using Neutral-Atom Arrays to Build Quantum Computers

Principle of operation

Performing computations with neutral atoms involves realizing, controlling, manipulating, and measuring neutral atom qubits. Let's dive into some of the details.

The advantages of neutral atoms

Nature's perfect qubits

Atoms are nature's perfect qubits, all identical to one another. They are simultaneously capable of storing and processing quantum information, without significant cryogenic requirements. This gives an edge over manufactured qubits that can suffer from imperfections.

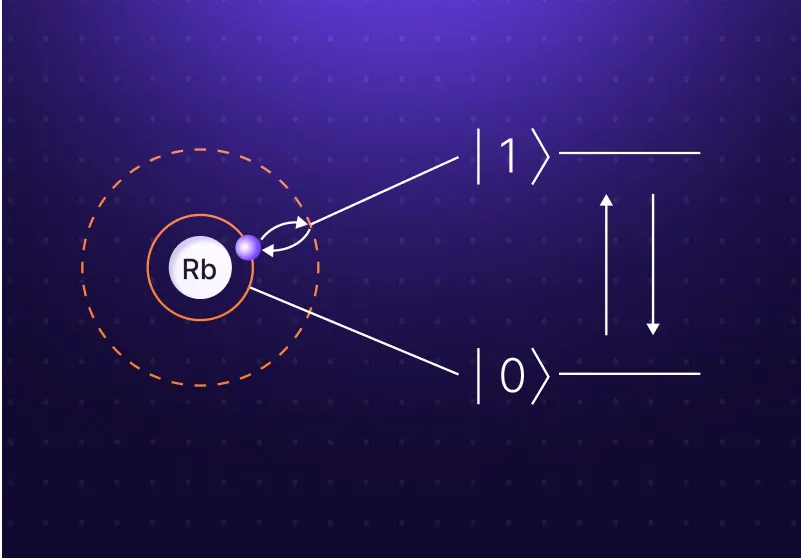

Our qubits are made of neutral atoms

Atoms consist of a nucleus and their electron cloud. At QuEra, we use Rubidium atoms. When the positive and negative charges of an atom balance each other, the atom is said to be neutral, just like most atoms are found in nature. By shining a laser at the atom, we can increase the energy of the atom, and excite it. Each atom has a wide range of potential excited states, each at different energy levels. This offers a great platform for storing and processing quantum information. Any choice of two such levels can be named ‘0’ and ‘1’ to form a qubit.

Controlled by lasers

We use lasers, acting as optical tweezers, to trap individual atoms in place. The lasers suppress atomic movement, effectively cooling the atoms down to nearly absolute zero temperature. At these temperatures, the individual discrete energy levels of the atoms can be resolved and manipulated, some of them leading to huge coherence times exceeding one second.

Error resiliency

Rydberg atoms interact on-demand. When atoms are not excited, they are resilient to errors regardless of the total number of qubits in the system. This significantly increases the computational power of our machines.

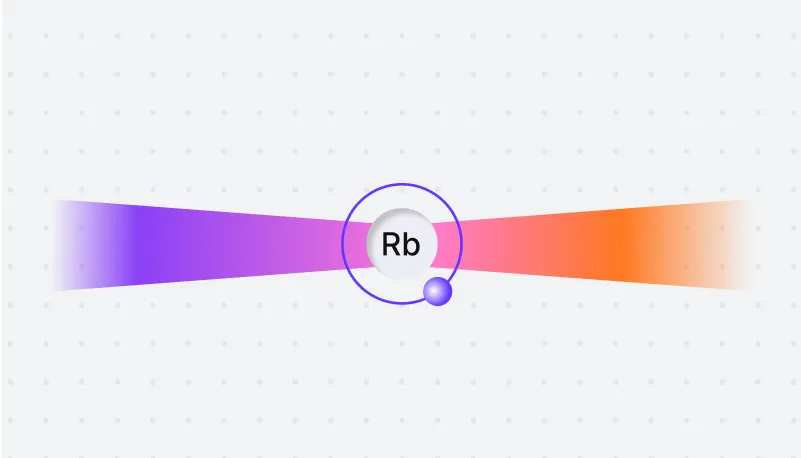

Perform computations by puffing-up atoms

When atoms are excited to high-energy states, called Rydberg states, their electron clouds puff up to a relatively enormous scale, about a thousand times their original size. In this Rydberg state, different atoms can interact over long distances, enabling quantum information to be transferred between them. This enables entanglement, one of the key ingredients for quantum information manipulation.

The interaction mechanism between Rydberg atoms is known as the 'van der Waals' interaction, which originates from the strong dipole moments of the expanded atoms. This interaction diminishes with the sixth power of the interatomic distance, implying that atoms interact intensely only when they are in close proximity. In fact, this interaction can become so powerful that it can induce the 'Rydberg blockade' effect, whereby no two adjacent atoms can be excited simultaneously. This mechanism enables the implementation of conditional quantum logic and two-qubit gates.

High-quality multi-qubit gates

Long-range Rydberg interactions can be used to reduce the gate-decomposition overhead of multi-qubit gates. This minimizes errors and increases processing speed.

Entangling multiple qubits

Remarkably, the size of Rydberg atoms can encompass several nearby qubits, allowing for mutual interaction. Unlike most quantum computers that can only implement native 1-qubit and 2-qubit gates, the Rydberg blockade mechanism facilitates the development of native multi-qubit gates.

Gates such as the Toffoli gate (refer to the image on the left) hold significant importance in numerous quantum algorithms. By natively encoding these multi-qubit gates, the circuit depth of the algorithm can be substantially reduced, thereby significantly mitigating errors. A prime example of this is the constant-depth implementation of Shor’s algorithm.

Small footprint

The atoms and control system for a neutral-atom quantum computer can easily fit in a room. This small footprint makes neutral atom computers easily deployable in a lab or a data center, without requiring cryogenic cooling.

A tiny footprint

All of this happens on a miniature scale: tens of thousands of laser-trapped atoms can be packed into an area smaller than a square millimeter. Furthermore, with the use of an acousto-optic deflector, a few lasers can achieve precise control over multiple qubits.

Field programmable qubit arrays (FPQA™)

The flexible arrangements of qubits enable reconfigurable layouts. This can be leveraged in algorithm design to limit gate overhead, leading to efficient circuits and significantly shorter development cycles. New applications requiring different configurations can be implemented without reassembly of the hardware.

Flexible configurations

Given that lasers can move freely through space, neutral atoms can also be arranged in almost any configuration. This flexibility allows for the adjustment and adaptation of qubit connectivity to meet the specific requirements of each problem. Additionally, it results in considerably shorter development cycles, as new applications can utilize new configurations without the need for hardware reassembly.

Highly scalable architecture

The small size and efficient control mechanisms allow for dramatic increases in the number of qubits without requiring interconnects. Since the number of control signals can be significantly lower than the number of qubits, high degrees of scaling become practical.

The core neutral atom processor can be equipped with modules for different functionalities, such as to enable digital quantum gates, error correction, memory, and processing zones.

Qubit shuttling

With an appropriate selection of atomic levels for qubit encoding, atoms can even be coherently moved during a calculation. This is a key benefit of neutral-atom technology. It facilitates an efficient memory bus service, allowing comprehensive connectivity of the qubits on a large scale. This is especially advantageous in error correction, as it presents new possibilities for gate selection and error-correcting codes. An example is Harvard's unique realization of Kitaev's paradigmatic toric code with periodic boundary conditions. Moreover, qubit shuttling enables zoned architectures for memory and processing, further enhancing the ratio of control lines to the number of qubits. Collectively, these features position neutral-atom quantum computers as the preferred architecture for utility and scalability.

Hybrid operation modes

The ability to work in analog or digital modes allows users to choose the optimal mechanism to reach high-quality solutions to the problems on hand.

The digital mode

The digital gate-based mode decomposes a complex operation into a few elementary steps (gates) that operate on one or two qubits at a time. The gates move qubits between their two computational states. Gate sequences change the computational state of the entire system from one state into another. When measured, the final state becomes a bit string, capturing the outcome of the computation.

Gate-based operation modes provides an elegant recipe to enable universal functionality and programmability, with only a small set of elementary operations.

The analog quantum mode

At the physical level, digital quantum operations are continuous state transitions expressed by a Hamiltonian: the function that describes the forces that make a physical system change over time. If one can control a Hamiltonian well-enough, the gate-based mode can be bypassed in favor of an analog computation mode. The analog mode is not as universal as the gate-based mode, but when it is possible, it leads us directly to answers without decomposing algorithms into elementary steps, avoiding many of the noise and coherence issues that are common in digital computation modes.

Post-classical compute power

Robustness to errors, combined with efficient control mechanisms enabled the assembly of our 256-qubit machine. This machine is powerful enough to enter a nonsimulatable regime for a range of practical problems, surpassing the capabilities of classical supercomputers.

Scalability vs. programmability

In the digital gate-based mode, errors can be introduced at each step, and accumulate over the course of a computation. In contrast, analog mode does not suffer from accumulation of faulty gates and is therefore much less susceptible to errors, making it very suitable for the current stage of quantum computing maturity.

Combined with simplified control requirements, the analog quantum mode enables efficient manipulation of many more qubits with significantly fewer control signals.