The quantum computing industry has reached an inflection point. With hundreds of millions of dollars flowing into quantum startups, government programs accelerating across allied nations, and vendors competing to demonstrate practical advantage, the challenge for buyers has shifted. The question is no longer "Is quantum computing real?" but rather "How do I evaluate which claims are credible, and which are premature?"

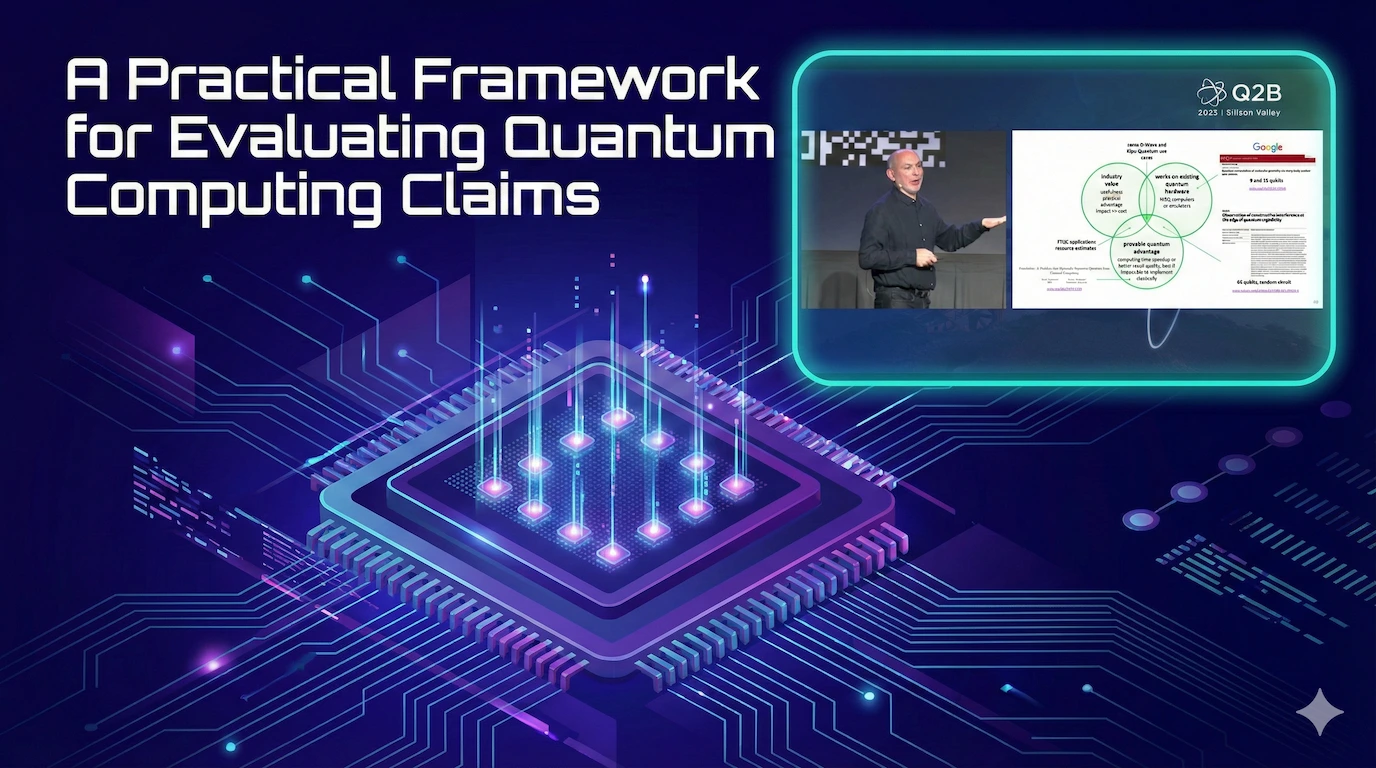

At Q2B25 Silicon Valley, Olivier Ezratty (author of the 1,500-page open-access book Understanding Quantum Technologies) presented a rigorous framework for evaluating quantum computing announcements. His approach cuts through the hype cycle by establishing clear criteria for what constitutes genuine progress. For HPC centers, government programs, and enterprise innovators weighing quantum investments, this framework offers a practical lens for due diligence.

The Three Dimensions of Quantum Value

Ezratty frames evaluation through a three-dimensional model. Any quantum computing claim can be assessed against three criteria:

1. Industry Value — Does the work address a problem that matters commercially or scientifically? Is there practical advantage or business value at stake?

2. Working Hardware — Has this actually run on a quantum computer? Not emulated, not projected, but executed on real hardware with real input data and real output results.

3. Provable Quantum Advantage — Is there demonstrated speedup, quality improvement, or resource efficiency versus the best classical alternatives? Can this be independently verified?

The intersection of all three dimensions is rare. Most work in quantum computing falls into partial categories, and understanding where a claim sits in this framework is the first step toward informed evaluation.

Mapping the Landscape: Seven Categories of Quantum Work

Using this three-dimensional lens, Ezratty identifies distinct categories of quantum computing claims:

Theoretical Papers occupy the space of provable advantage without hardware execution or industry application. These are important for advancing the field but do not constitute near-term value propositions. The Forrelation algorithm, with potential signal processing applications, exemplifies this category.

Proof-of-Concept Demonstrations run on real hardware but neither solve industry problems nor demonstrate quantum advantage. They show the machine works, which is necessary but not sufficient.

Quantum Supremacy Experiments (like Google's random circuit sampling) achieve provable advantage on real hardware but solve problems with no commercial application. Google's OTOC experiments fall here: academically significant at 9-15 qubits, but not industrially useful.

Toy Model Case Studies address real industry problems on real hardware, but at sub-scale sizes without proven advantage. Many vendor announcements fall here: legitimate progress, but the problem instance is too small to draw conclusions about production viability.

Quantum-Inspired Solutions are classical algorithms developed through quantum research. These deliver real value but do not require quantum hardware. They represent an important spillover benefit from quantum R&D but should not be conflated with quantum computing itself.

Prospective Use Cases have identified industry value and theoretical quantum advantage but await fault-tolerant hardware. Drug discovery simulation at production scale is the canonical example: we know the algorithms, we know the value, we need the machines.

Useful Case Studies occupy the center of the framework: real hardware, real industry value, and demonstrated quantum advantage. Ezratty cited recent work from Phasecraft as approaching this standard, though he emphasized that even these examples have not yet reached full industry scale.

The Five-Point Assessment Framework

Beyond categorization, Ezratty proposes five specific criteria for assessing any quantum computing claim:

1. Problem Size

Is this an industry-scale problem or a toy model? A 10-city traveling salesman demonstration is interesting; a 10,000-city instance is relevant. Ask explicitly: "What is the data size? How does this compare to production requirements?"

2. Resource Estimates

How many qubits (logical and physical) are required? What gate depth? What computation time? Reputable work specifies these numbers. Absence of resource estimates is a red flag.

3. Nature of Advantage

Quantum advantage can manifest as speedup, solution quality, data efficiency, or energy reduction. Not all advantages are equal. Enterprise buyers typically require 10x return on investment; incremental improvements rarely justify quantum's operational complexity. Be specific: "What exactly is the claimed advantage, and what is the magnitude?"

4. Classical Benchmarking

This is perhaps the most critical criterion. Ezratty warns: "Don't reverse the burden of proof." Before assuming quantum will help, understand classical capabilities. What is the best available classical solution? Has the quantum result been compared against it rigorously? DARPA's approach, reasoning by software pipelines rather than just hardware, exemplifies this discipline. Notably, Ezratty observed that over the past five years, more progress has come from software optimization than from hardware improvements.

5. Documentation Quality

An arXiv preprint is the minimum bar; peer-reviewed publication is preferred. Documentation should include: logical and physical qubit counts, business benefit metrics, solution cost, and data sizing. Marketing announcements without technical papers should be treated with appropriate skepticism.

Where the Evidence Points

Applying this framework across market segments reveals uneven progress:

Fundamental Physics shows the strongest evidence. Documented case studies exist where quantum systems have produced scientific insights beyond classical simulation capabilities. This is where neutral-atom platforms have demonstrated particular strength, with peer-reviewed publications in Nature documenting observations (like string breaking and fermionic system simulation) that validate quantum computing's research value.

Chemical and Materials Simulation represents the most optimistic near-term opportunity. Electronic structure calculations, molecular dynamics, and catalyst design are areas where quantum advantage is theoretically grounded and experimental progress is measurable. The challenge remains scaling to industrially relevant problem sizes.

Optimization, Machine Learning, and PDEs warrant more skepticism. Ezratty noted that these domains lack the exponential speedup algorithms that characterize quantum's clearest advantages. A recent paper by Marco Cerezo and collaborators argues that quantum machine learning advantage requires either quantum data sources or quantum RAM (which does not yet exist). Most QML studies, Ezratty observed, lack proper data sizing documentation, making claims difficult to assess.

What Buyers Should Ask

Ezratty's advice to enterprise and government buyers is direct: be pushy. Demand quantitative answers to specific questions:

• What are the resource estimates for this application at production scale?

• How does this benchmark against the best classical solution available today?

• What peer-reviewed documentation supports these claims?

• What is the quantified economic benefit, and what assumptions underlie it?

• Has this been run with real input data and produced verifiable output results?

Vendors who can answer these questions with specificity have done the work. Those who deflect to future roadmaps or marketing language have not.

The Path Forward

IBM's public roadmap projects hundreds to thousands of logical qubits by the early 2030s. Other vendors have announced similar timelines. As the industry transitions from NISQ to fault-tolerant systems, the evaluation framework Ezratty proposes becomes more, not less, important.

The coming years will see an acceleration of both genuine progress and inflated claims. Government programs like DARPA's Quantum Benchmarking Initiative are explicitly designed to separate signal from noise, selecting vendors who can demonstrate measurable progress toward utility. Enterprise buyers can apply similar rigor.

The quantum computing field is advancing rapidly. But rapid progress does not excuse imprecise claims. By applying Ezratty's framework, stakeholders can engage with quantum computing's genuine potential while maintaining the skepticism that responsible investment requires.

---

See the full presentation at:

e%201437254775.png)

.webp)