QuEra's journey from analog simulation to fault-tolerant quantum computing

At Q2B Silicon Valley this December, Tommaso Macrì took the stage to share something remarkable: the story of how neutral-atom quantum computing has evolved from laboratory curiosity to hybrid supercomputer integration—and why the pieces are finally falling into place for fault-tolerant quantum computing.

The message was clear: we're not just building quantum computers anymore. We're building the bridge to a fault-tolerant future.

Nature's Perfect Qubit

The promise of neutral atoms lies in their fundamental physics. Every rubidium atom responds identically to external fields—what QuEra calls "nature's perfect qubit." This isn't marketing speak; it's a manufacturing advantage that eliminates the fabrication variability plaguing other approaches.

But the real story isn't just about identical qubits. It's about what you can do with them.

Neutral-atom systems enable massively parallelized quantum operations—executing many gates simultaneously rather than one at a time. This capability becomes critical when running algorithms that require multiple cycles of quantum error correction. And because these systems don't need the extreme cryogenic cooling that superconducting chips demand, they operate with dramatically smaller footprints and energy bills.

These advantages sound theoretical until you see them deployed. QuEra's Aquila system has been running on Amazon Braket since November 2022, available 130 hours per week. More than 40 peer-reviewed papers have been published using the system—most without any direct assistance from QuEra's team.

Scientific Discovery at Scale

The breadth of research happening on Aquila speaks to the maturity of the platform. Industry leaders in logistics, financial services, and pharma have published results. But some of the most compelling work comes from pure scientific curiosity.

Recent collaborations with Harvard and the University of Innsbruck produced a Nature paper on lattice-based theories in two dimensions—work inspired by applications in high-energy physics. Researchers have explored equilibrium and non-equilibrium dynamics in many-qubit systems relevant to understanding complex materials. Quantum machine learning algorithms have been executed with hundreds of qubits, both for classification and regression tasks.

One partnership particularly illustrates what's possible when quantum hardware meets scientific ambition.

At NERSC—Lawrence Berkeley National Lab's computing center—researchers are using Aquila through a program called QCAN to develop scientific applications. The machine functions as a high-fidelity simulator of an extended quantum Ising model with independently controllable transverse and longitudinal fields. Users can program not just the field parameters but the actual geometry of the atoms, arranging them in one or two dimensions to match their problem structure.

What emerged from this collaboration was published just this October: a deep characterization of the transition from a thermal to a pre-thermal phase. The physics is fascinating—thermalization is a concept borrowed from classical physics where a small system in contact with a larger reservoir reaches equilibrium. The team discovered that for certain parameter ranges, the experimental observables match thermal predictions precisely. But for other values, they diverge systematically through a mechanism called pre-thermalization, where the system cannot explore its full available Hilbert space.

The scale of these simulations matters. The observations extend to systems with up to 180 qubits—far beyond what even advanced numerical techniques like tensor networks can handle.

The Digital Transition

Aquila demonstrates what analog quantum computing can deliver today. But the path to universal quantum computing requires digital, gate-based operation—and that's where Gemini enters the picture.

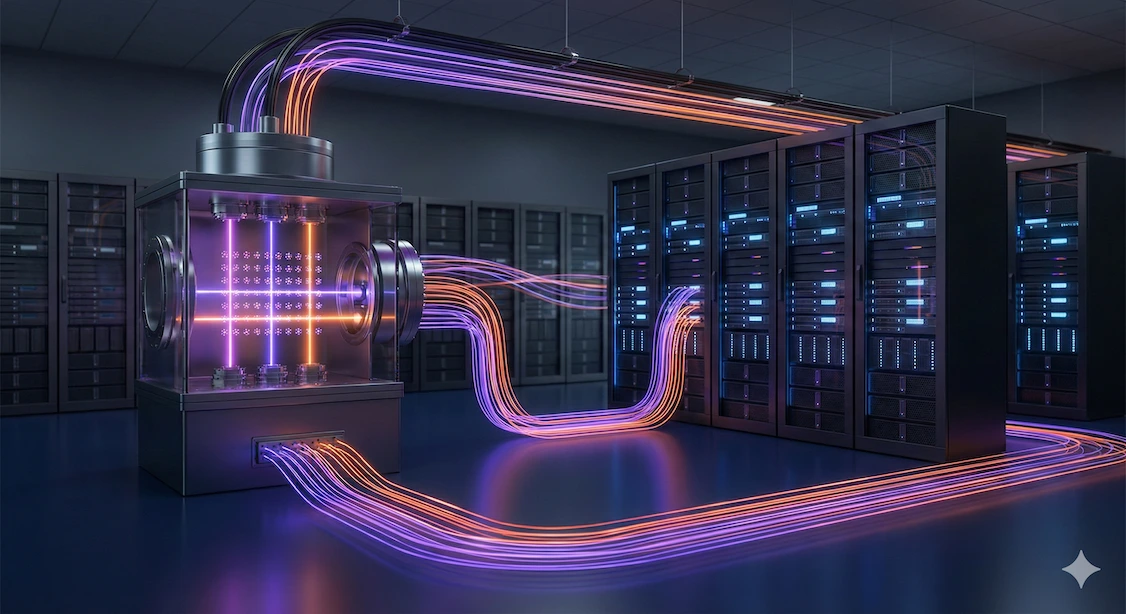

Gemini is QuEra's second-generation system: 260 qubits operating in digital mode. The system was deployed at AIST (Japan's equivalent of NIST) and inaugurated in March 2025 in the presence of former Japanese Prime Minister Ishiba and QuEra President Takuya Kitagawa.

What makes this deployment historically significant isn't just the hardware. Gemini is being integrated with ABCI-Q, a classical supercomputing system powered by approximately 2,000 NVIDIA GPUs. This creates what is effectively the world's first hybrid quantum supercomputer.

The technical capabilities enabled by Gemini's architecture are substantial. The system can physically shuttle atoms around the computational zone, enabling massive parallelism and the execution of transversal gates essential for quantum error correction demonstrations.

Life Science on the Horizon

One of the most ambitious applications QuEra is pursuing with Gemini involves the Wellcome Leap Foundation's Quantum4Bio program, a 30-month initiative now in its third phase.

Two teams out of six have advanced to Phase 3, each targeting a distinct life science application. The first, with the University of Nottingham and Phasecraft, applies quantum computing to myotonic dystrophy, a severe genetic disease. The second, in collaboration with Harvard, MIT, and the Broad Institute, focuses on ligand-protein binding affinity simulation.

The technical approach exemplifies the co-design philosophy that neutral atoms enable. Rather than forcing problems into hardware constraints, the team leverages the high parallelizability and long-range connectivity of neutral-atom systems to dramatically reduce circuit depth. This isn't theoretical optimization—hardware-efficient ansätze designed specifically for the architecture outperform literature approaches on both circuit depth and accuracy.

There's appropriate humility here. These variational methods aren't guaranteed to scale, and they rely on noisy hardware. Today's quantum computers make mistakes every few hundred or few thousand operations at best. Tackling the problems that truly matter—quantum chemistry, cryptography—requires error rates orders of magnitude smaller.

Which brings us to quantum error correction.

The Error Correction Moment

QuEra has devoted substantial effort to proving that quantum error correction is feasible on neutral-atom systems. The progress has been methodical and increasingly impressive.

Two years ago, the team demonstrated a logical qubit architecture with up to 48 logical qubits. The architecture mirrors classical computing systems, with distinct storage, entangling, and readout zones. More recently, they achieved logical magic state distillation—an essential tool for demonstrating a universal gate set at the logical qubit level. This demonstration was realized on Gemini before the system shipped to Japan.

Theoretical advances have matched the experimental work. Quantum error correction can now be embedded into larger, more complex algorithmic designs relevant for utility-scale applications. New tools—correlated decoding, algorithmic fault-tolerant approaches—promise to dramatically reduce the space and time costs of error correction. Machine learning approaches developed with NVIDIA partners are improving decoder quality.

The collaboration with Harvard has pushed these demonstrations further still. The team has demonstrated continuous operation of systems with more than 3,000 qubits—a milestone that also addresses atom loss, one of the fundamental challenges in neutral-atom systems. Even more striking: the Harvard team, led by QuEra co-founder Mikhail Lukin, demonstrated deep logical quantum circuit execution with up to 96 logical qubits and more than 400 physical qubits.

Integration, Not Isolation

The technical achievements matter. But what makes this moment different is the conviction that the core architecture for quantum error correction has been demonstrated and validated.

The remaining work is integration—combining all the elements to accelerate adoption across industry, the HPC community, government, and academia. This is why the QuEra Quantum Alliance exists: a structured partnership model to collaborate with industry leaders across every layer of the quantum computing stack.

This isn't the story of a technology waiting for its moment. It's the story of a technology actively assembling the pieces for what comes next.

The analog foundation is proven. The digital transition is underway. Quantum error correction is demonstrably feasible. And the first hybrid quantum supercomputer is already operational.

What remains is execution—and the conviction that neutral atoms have shown the way forward.

Watch the full video here:

.webp)