How QuEra's SDK evolution mirrors the transition from analog to digital quantum computing

As neutral-atom quantum computing moves from analog simulation to digital gate-based operation, the software has to evolve too. At Q2B Silicon Valley, Philip Weinberg walked through what that evolution looks like in practice—and why the abstractions matter as much as the hardware.

The message: programming a neutral-atom quantum computer isn't like programming any other quantum device. The SDK should reflect that.

Why a New Stack?

QuEra started as an analog quantum computing company. The original Bloqade SDK was built to program Aquila, the 256-qubit analog processor that's been running on Amazon Braket since 2022. That SDK still exists—now renamed Bloqade Analog—and will be supported as long as analog processors remain in service.

But digital quantum computing introduces fundamentally different programming requirements. Atoms move. Gates happen in parallel across different zones. The control over when and where operations occur becomes granular in ways that analog mode never required.

The new stack has two major components: Bloqade Circuit for high-level circuit programming, and Bloqade Shuttle for low-level atom movement control. Both are embedded in Python, designed to integrate with existing workflows—whether that's Qiskit, Cirq, or something else entirely.

Bloqade Circuit and SQuIN

Bloqade Circuit provides the entry point most quantum programmers will recognize: a circuit-level SDK where you define gates and operations on qubits.

But the intermediate representation underneath—called SQuIN—incorporates something most quantum IRs lack: structured control flow. Quantum instructions mix with for loops, if statements, closures, and functions. This isn't just syntactic sugar; it's a design decision rooted in how neutral-atom hardware actually operates.

The reason is parallelism. Neutral-atom platforms are highly parallelizable. You can broadcast an X gate across a sequence of qubits simultaneously—SIMD-style instructions are first-class citizens in both the IR and the syntax. That parallelism needs to be expressible at the programming level, not bolted on afterward.

Integration points matter too. Bloqade Circuit supports OpenQASM 2 directly, with Cirq integration available and QIR integration in progress. Once you enter the compiler pipeline, you can go downstream to hardware or use the built-in simulator based on PyQrack (a Unitary Fund project). For error correction work, Stim integration allows generating equivalent Stim programs from SQuIN kernels.

The structured control flow becomes particularly valuable for QEC. You can define basic error correction primitives, then use the toolchain to simulate and reason about quantum error correction at a higher level of abstraction.

Bloqade Shuttle: Programming Atom Movement

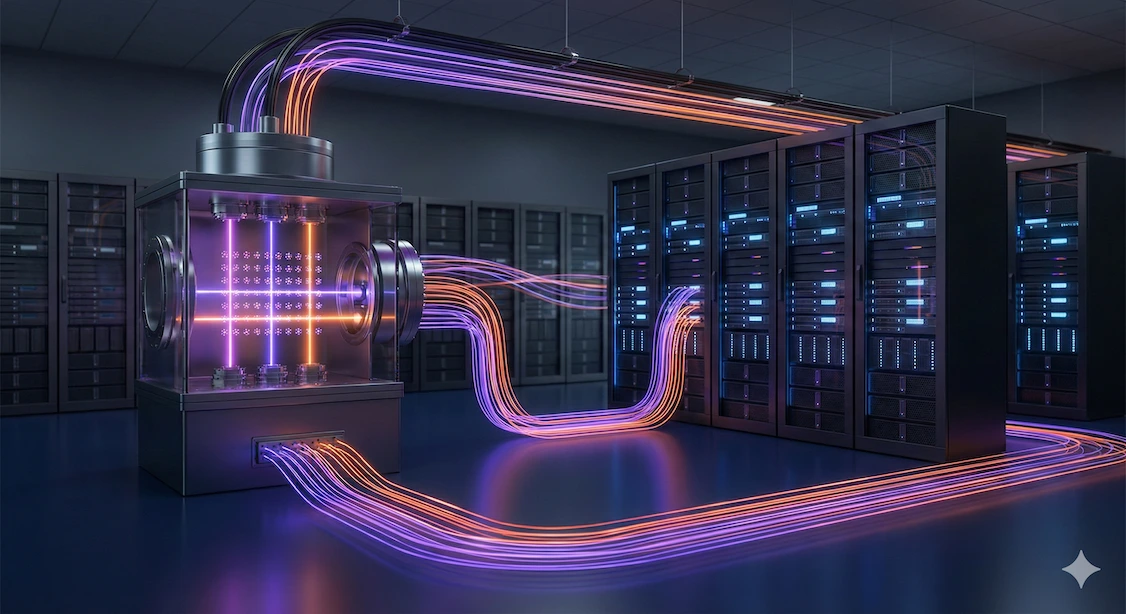

Below the circuit level sits Bloqade Shuttle—and this is where neutral-atom programming becomes genuinely different from anything else in the quantum software landscape.

Inside a neutral-atom processor, optical tweezers pick up atoms and move them around a two-dimensional plane. The positions of traps, the sequence of movements, which traps are active at which times—all of this is programmable. Bloqade Shuttle provides the SDK for defining these low-level hardware operations and packaging them into higher-level abstractions.

Think of it this way: a "move" in Shuttle is effectively on the same level as a gate. You define a kernel that specifies trap positions, movement sequences, and timing. Then you assign that kernel to hardware resources and compose it with other operations.

Here's why this matters. When you move atoms into an entanglement zone, apply a CZ gate (the "top-hat" laser pulse that shines on a specific region), and move them back, each step has associated noise characteristics. Encapsulating moves as first-class objects allows the toolchain to model error from both gates and movement together—capturing the full noise character of the machine.

The visualization tools make this concrete. You can see still frames or animations showing exactly what a kernel does: dots representing atoms, arrows showing movement paths, dashed-to-solid transitions indicating trap activation, red bands marking CZ pulse regions. This isn't just pretty pictures; it's debugging infrastructure. When your compiler generates unexpected behavior, you can watch what it actually does.

Grid Abstractions and Hardware Modeling

Atom positions are defined using grid objects—reflecting how optical tweezers are actually configured. The SDK provides extensive support for grid manipulation: slicing, indexing, shifting, scaling, and combining operations to define the paths atoms take during execution.

This level of control enables something important: modeling exactly what a quantum device will do before you run on hardware. Given a particular move architecture, you can estimate noise characteristics. Given a SQuIN circuit, you can compile it down to a move architecture and get animations showing the execution flow.

The GHZ state preparation example illustrates the power of this approach. You can implement log-depth GHZ state prep with multiple pairs of atoms, watch the compilation result as an animation, use it to debug both architecture and compiler, then lower to hardware signals once you're confident everything works.

Building a Common IR for Atom Shuttling

One of the most interesting aspects of the Bloqade Shuttle work is the ambition to create shared semantics across the neutral-atom ecosystem.

Multiple groups are working on neutral-atom compilers—academic projects like ZAC (Zone-Aware Compiler) from UCLA, as well as proprietary efforts. Each makes different assumptions about how to represent atom movement. A unified IR that multiple compilers can target would accelerate the entire field.

The roadmap includes converging on that IR, automating move assignment across multiple devices, and building shared emulation capabilities. Fidelity estimation, atom position analysis (ensuring atoms don't collide), and other common tools could benefit anyone targeting neutral-atom hardware—not just QuEra customers.

The Kirin Compiler Toolchain

Underlying both Bloqade Circuit and Bloqade Shuttle is Kirin, a compiler toolchain for building embedded DSLs in Python.

The design philosophy follows MLIR: build up small semantic pieces that can be shared across different compiler toolchains. Both the circuit-level and shuttle-level SDKs use the same SSA IR, allowing flexible switching between representations.

Key capabilities include dialect definition, direct Python AST integration, abstract interpretation for data flow analysis, IR interpretation for debugging, optimization passes, and code generation to non-Kirin intermediate representations. The strongly-typed system handles the complexity that arises when embedding structured semantics in a dynamically-typed language like Python.

For the compiler-curious: Kirin is open source alongside Bloqade Analog, Bloqade Circuit, and Bloqade Shuttle.

What's on the Roadmap

The 2025-2026 roadmap reflects lessons learned from initial deployment. The original IR, while flexible, proved difficult to compile efficiently. Simplification work is underway (tracked in PR #492 on the Bloqade Circuit GitHub).

CUDA-Q and QIR integration is prioritized for GPU-accelerated simulation performance. Stim code generation is improving, with a focus on compiling SQuIN for loops down to Stim repeat statements—important for error correction simulation at scale.

For Bloqade Shuttle, the priorities are IR convergence with other neutral-atom compiler projects, move automation across multiple devices, and expanded emulation capabilities.

Getting Started

Both packages are open source and pip-installable:

pip install bloqade-circuit

pip install bloqade-shuttle

For application developers: the structured control flow in SQuIN—for loops, if statements, parallelization—offers expressive power specifically designed for neutral-atom hardware. Experimenting with these constructs is the best way to understand what the platform enables.

For compiler developers: Bloqade Shuttle provides a window into the low-level semantics of atom shuttling. Understanding optical tweezers, tone assignment, and move encapsulation helps when optimizing for neutral-atom targets.

For integration work: OpenQASM and QIR pathways into the compiler stack are available. Issues with either can be addressed through direct integration into SQuIN.

Monthly community meetings provide direct access to the development team, and contributions—documentation edits, feature requests, bug reports, pull requests—are welcome.

The documentation lives at bloqade.quera.com, with examples, tutorials, and background material on neutral-atom quantum computing.

Watch the full presentation:

.webp)

.webp)