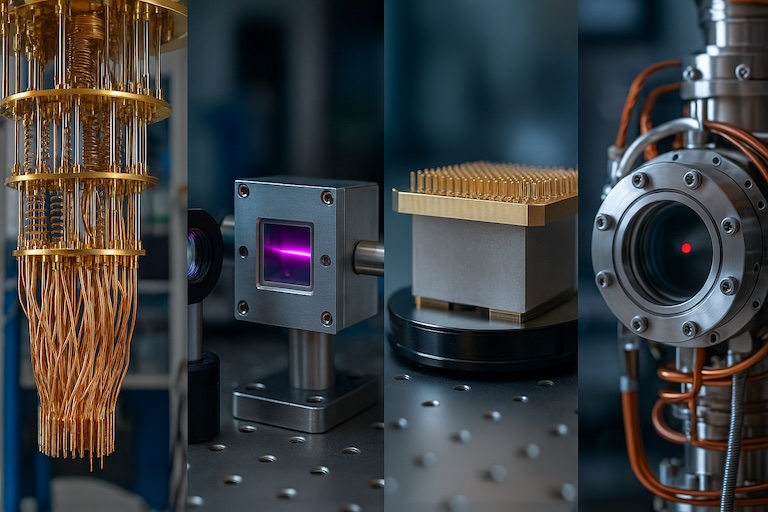

Synopsis: HPC managers don’t need a crash course in quantum mechanics; they need a clear sense of what kinds of machines are being built, what those machines demand from their facilities, and which roadmaps are actually demonstrating error reduction at scale. Today’s serious candidates fall into five buckets: superconducting circuits, trapped ions, neutral atoms, photonic systems, and semiconductor spin qubits. (You’ll also hear about topological qubits—promising, but still pre-product.) Below is a plain-English tour of where each stands and what it means for integration into HPC environments.

Superconducting circuits (IBM, Rigetti,IQM, and others) are industrialized today. They live inside dilution refrigerators at ~10–20 mK, and the engineering is now focused on improving qubit quality at scale while gradually evolving the surrounding infrastructure toward data-center compatibility. The most meaningful progress lately has been in demonstrating “logical qubits” which bundle several physical qubits with the goal of improving their error rate. In 2024, Google demonstrated such work on its “Willow” processors, and IBM had their own interesting demonstrations. These results don't make the cryogenics smaller, but it does validate the core premise that smart scaling can reduce errors. For planners, this means superconducting stacks will keep demanding power and footprint, and the eventual systems will likely spread across multiple networked cryogenic modules. In other words, they are a modality with a solid peer-reviewed path toward large-scale error correction—but one that will push facilities toward cluster-like quantum deployments rather than a few standalone machines.

Trapped ions (Quantinuum, IonQ and others) using individual ions (charged atoms) as qubits. They operate in ultra-high vacuum with laser control and, at modest sizes, offer all-to-all connectivity on small machines and excellent fidelities (error rates). Multiple groups have published rigorous benchmarking and architectural work that maps how to scale beyond a single ion chain, including shuttling architectures and dynamic optical potentials. The upside is high-quality gates and flexible connectivity; the tension is speed and scaling complexity as you push towards many interacting ions with stable control. For HPC teams, trapped ions look like well-behaved instruments that you can schedule today for algorithmic prototyping, with active research on the networking needed for bigger machines.

Neutral atoms (QuEra, PASQAL, and others) arrange identical atoms in optical-tweezer arrays and physically reconfigure them during a program, which gives compilers a way to create effective all-to-all interaction patterns without wiring every neighbor. From a facility standpoint, these machines run with lasers and vacuum chambers near room temperature—no dilution fridge—though they do require vibration control and automated calibration of large optical systems. What matters is that neutral-atom teams have shown logical qubit milestones, including experiments with tens of logical qubits and the first demonstrations of key ingredients for universal fault-tolerant computing. The significance for procurement is not that neutral atoms are “easier,” but that they’re accumulating credible evidence of progress at the level HPC users ultimately care about (logical qubits, algorithm depth), while keeping facility demands closer to classical optics labs than cryo bays.

Photonic systems (PsiQuantum, Xanadu and others) encode qubits in light. Their long-term promise is compelling for network-scale systems and modularity, and measurement-based schemes are expressly designed to tolerate significant photon loss—one of the toughest issues in photonics. The integration story is nuanced: much of the photonic stack can operate at or near room temperature, but the best single-photon detectors today are superconducting and still need cryogenics, which shifts (rather than erases) facility requirements. Recent publications and company disclosures describe manufacturable photonic chipsets and plans for “datacenter-sized” facilities; treat these as serious R&D directions. For planners, the significance is clear direction and serious investment, but with due diligence needed around which subsystems still require cryogenics, and how industrial supply chains for detectors, lasers, and foundry partnerships mature.

Semiconductor spin qubits (Intel, Diraq, and others) leverage CMOS-compatible nanofabrication and promise high density and on-chip control. The physics is mature enough that you’ll now see single- and two-qubit operations with high fidelities and rapid advances in readout and coupling, but coherent control across many uniform qubits is still an active area of work. For HPC strategists, silicon spins are the most “semiconductor-industry-native” path, which matters for eventual cost and supply chain, yet the near-term operational picture still looks like careful lab instruments rather than drop-in accelerators. Keep an eye on demonstrations that standardize fidelity across arrays and show practical, thermal-budget-aware control electronics.

Where does quantum annealing (D-Wave and others) fit? Annealers aren’t universal gate-model machines; they target a narrower class of optimization and materials-simulation problems. The reason they remain in the conversation is that annealing hardware has recently shown goodl performance on specific useful problems. There is an active (and healthy) debate as classical algorithms improve and chase the same benchmarks. For HPC, the takeaway is that annealers can be useful specialized accelerators in workflows you already run (optimization, sampling), but they are not substitutes for the gate-model systems needed for the full suite of quantum algorithms and applications.

A practical way to read this landscape is to ask two questions. First: what does the platform demand from your building? Superconducting circuits and many spin-qubit experiments anchor you to millikelvin cryogenics and dense RF/control wiring; the technology is advancing (and even exploring higher-temperature qubits), but your facilities team will be part of the project from day one. Trapped-ion and neutral-atom machines shift the burden to lasers and environmental stability, which may feel more familiar to labs with precision optics. Photonics splits the difference: the logic may be room-temperature, but top-tier detection remains cryogenic for now. Second: where is the strongest path to truly-useful quantum computers? On that front, the most advanced results have been published by neutral-atom groups. This is the axis that separates headline qubit counts from systems that your users can rely on.

Finally, a word on topological qubits (Microsoft). The allure is built-in error resistance via exotic quasiparticles. Microsoft has published some interesting - yet controversial - papers. These are genuine scientific advances, but from an HPC-planning perspective they are signals to watch, not procurement options to evaluate—yet.

Bottom line: If you’re choosing a platform to learn inside an HPC program, match your constraints to the modality’s strengths. Keep the bar high: require results that show improving scale and error rates, operational stability data, and concrete integration into your scheduler and observability stack. That’s how you convert a hardware modality into something your users—and your budget committee—can trust.

.webp)