The quantum computing industry has a credibility problem. As venture capital flooded the space over the past decade, so did inflated claims, premature commercial promises, and what one prominent researcher bluntly calls "snake oil."

For enterprise technology leaders evaluating quantum computing partnerships, this presents a genuine challenge: How do you separate the companies making real progress from those optimized for investor presentations?

In a recent interview on The Quantum Bull (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0_7SH3Eons0), Scott Aaronson, one of the world's foremost authorities on quantum computing theory, recently offered a framework that cuts through the noise. His perspective, grounded in 25+ years of academic research and independent of any commercial interest, provides the kind of evaluation criteria that enterprise buyers might find useful.

The Two-Qubit Gate Test

When vendors tout impressive qubit counts, Aaronson suggests looking elsewhere entirely.

"The most important number that I would look at is like the accuracy of a two-qubit gate," he explains. "People are constantly trying to talk about the number of how many qubits does this person have or that person have. But the number of qubits is completely irrelevant if the qubits are garbage."

This single insight can save enterprise buyers months of misdirected evaluation. Qubit count is easy to market but meaningless without quality. The real question is: how accurately can those qubits actually perform the operations that matter?

"The bottleneck there has always been the two-qubit gates, the ones that can produce entanglement," Aaronson notes. This is where quantum computing's power comes from, and where inferior hardware reveals itself.

The Snake Oil Tells

Aaronson is remarkably direct about the warning signs that should trigger skepticism:

"When people are talking about that the big use of a quantum computer is to solve optimization or machine learning problems or to turbocharge AI, or that it can already do this, it's already delivering value to customers in these areas or that it's doing it by simply trying all the possible answers in parallel and then just sort of magically picking the best one—these are the tells that you are dealing with a snake oil salesman."

This is a critical filter. The legitimate applications of quantum computing are well-established in scientific literature: simulating quantum physics and chemistry, certain defense applications, and potentially advantages in some optimization problems. Claims that go far beyond these, suchas current commercial value in AI or general optimization, should prompt serious scrutiny.

The Questions That Matter

Aaronson offers a simple evaluation framework:

"Does this actually beat what a classical computer could do for the same task? Did you test that? What is the evidence? What is the best classical algorithm for this task? What is the best quantum algorithm? Are you talking about a Shor-type speedup? Are you talking about a Grover-type speedup? What quantum speedup are you talking about?"

He concludes: "If people knew enough to just ask those kinds of questions and insist on answers, that would cut out like 90% of the BS that there is in this field."

For enterprise buyers, this translates into a straightforward vendor evaluation checklist:

- Ask for classical baselines. Any claimed quantum advantage should be benchmarked against the best-known classical algorithm for the same problem—not a strawman comparison.

- Require specificity on speedup type. Legitimate quantum advantages come from specific algorithmic structures. Vendors should be able to explain which quantum algorithm provides their advantage and why.

- Verify the demo. "I can mostly just judge things by looking at what demos have they actually done," Aaronson says. Published, peer-reviewed demonstrations carry weight. Marketing claims do not.

The Hardware Reality Check

When assessing modalities, Aaronson provides a clear-eyed assessment of where the field stands:

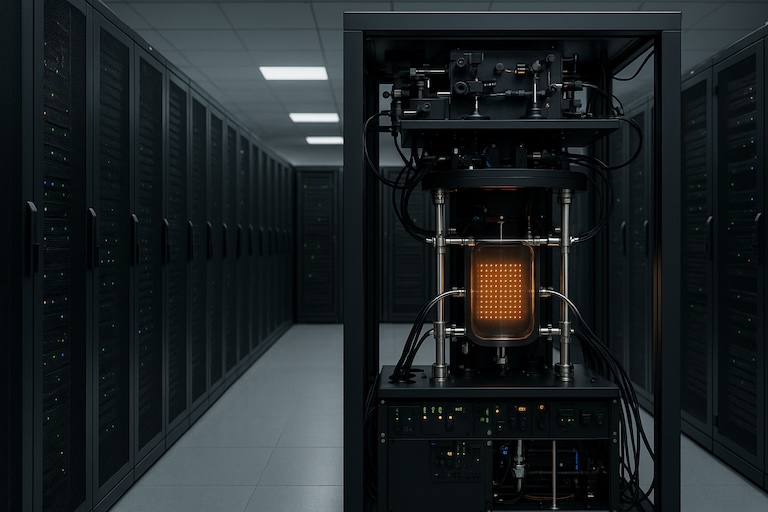

"The three approaches that are furthest along right now and what they've actually demonstrated in various ways would have to be superconducting qubits and trapped ions and neutral atoms."

Each has distinct characteristics:

- Neutral atoms are "winning right now in how many qubits they can do experiments with"

- Superconducting qubits are fast (billions of operations per second) but limited to nearest-neighbor connectivity on fixed chips

- Trapped ions are slower but offer programmable movement and, like neutral atoms, all-to-all connectivity

On gate fidelity "trapped ion is in the lead right now in terms of the accuracy of a two-qubit gate, which is now above 99.9% with superconducting and neutral atom just a little bit behind."

The Public Market Warning

Perhaps the most uncomfortable truth Aaronson shares concerns the relationship between commercial success and technical progress:

"There are companies that I see as really trying to solve the hardware problems. They might succeed, they might fail, but they're really focused on solving the real problems, talking about it more or less honestly. And then there are companies that have focused on marketing themselves to retail investors and doing IPOs. I see these two sets of companies as being mostly disjoint from each other."

This doesn't mean public companies can't deliver value. But Aaronson suggests that IPO status and stock performance are poor proxies for technical capability. Enterprise buyers should weight science and demonstrated results over market capitalization.

A Framework for Vendor Evaluation

Based on Aaronson's insights, enterprise buyers can apply a structured evaluation approach:

Technical Credibility

- Does the vendor publish peer-reviewed results?

- Can they explain their specific quantum advantage mechanism?

- Do their claims align with established quantum algorithms?

Honest Communication

- Do they acknowledge limitations and challenges?

- Are classical baselines provided for claimed advantages?

- Do they distinguish between current capabilities and roadmap targets?

Hardware Progress

- What are their two-qubit gate fidelities?

- Have they demonstrated error correction?

- Is their qubit count meaningful given their gate accuracy?

Business Model Alignment

- Is the company focused on solving hardware problems or raising capital?

- Do their partnerships involve real technical integration or press releases?

- Are they building toward applications where quantum actually provides advantage?

The Bottom Line

Quantum computing is entering a genuinely exciting phase. The hardware is approaching the fault-tolerance threshold that theory predicted decades ago. Real quantum advantages have been demonstrated for specific problems. Error correction is working.

But the gap between legitimate progress and marketing claims remains vast. Enterprise buyers who approach this space with informed skepticism can separate signal from noise.

As Aaronson puts it: "Quantum computing is not just this magic pixie dust that speeds up everything. If you want to speed up, it should be connected to one of the quantum algorithms that we actually know."

The companies that understand this—and can demonstrate it—are the ones worth watching.

.webp)