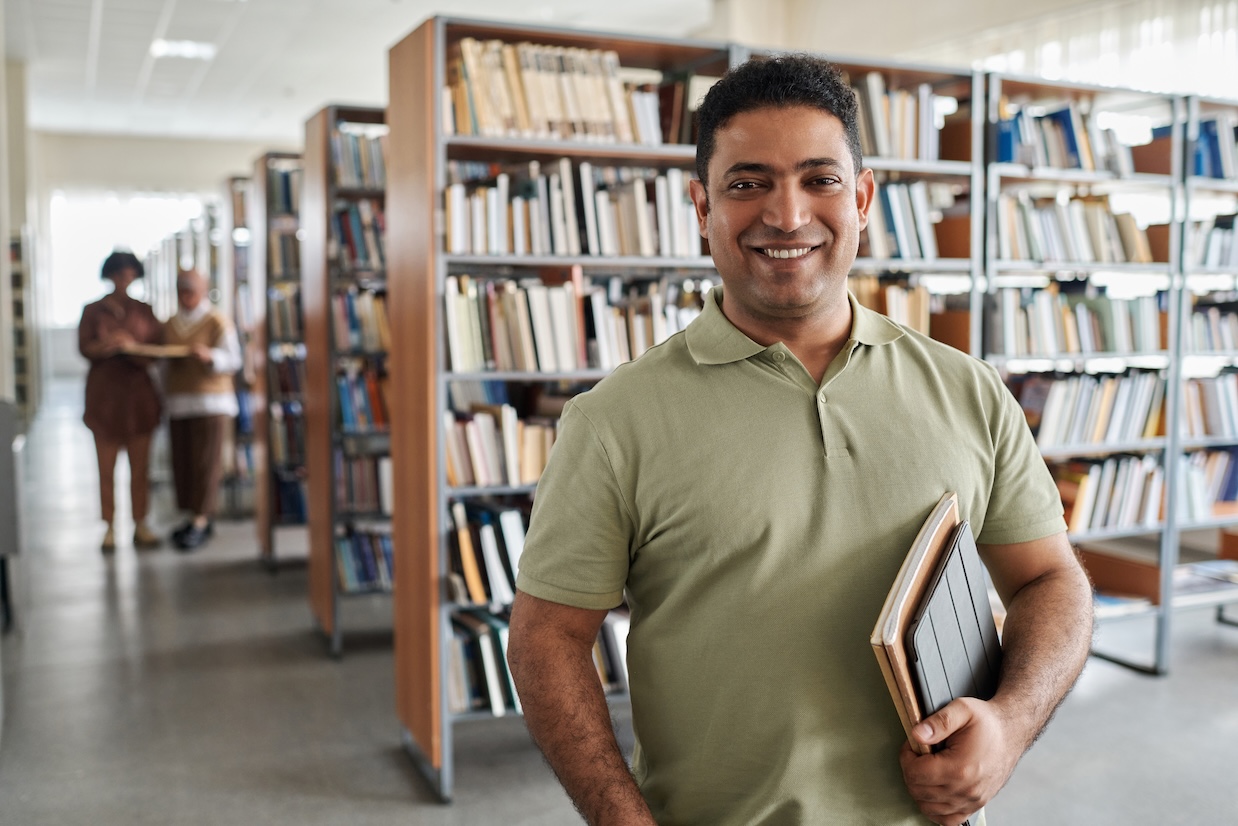

For an industry often accused of overpromising, the most valuable validation sometimes comes not from press releases or quarterly earnings calls, but from those with no financial stake in the outcome. Scott Aaronson is one such voice.

As a theoretical computer scientist at the University of Texas at Austin, founding director of UT's Quantum Information Center, and a researcher who has spent more than 25 years studying the fundamental capabilities and limits of quantum computation, Aaronson has watched the field evolve from academic curiosity to commercial race. He writes for Scientific American and the New York Times, and maintains a widely-read blog where he discusses everything from complexity theory to the claims made by quantum computing companies.

In a recent interview on The Quantum Bull (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0_7SH3Eons0) , Aaronson offered a measured and credible assessment of where quantum computing actually stands as we enter 2025. His verdict? The hardware "has met or exceeded" his expectations. And for a theorist who has spent decades watching the distance between theory and experiment slowly close, that's a significant statement.

The Gap Has Finally Closed

Aaronson frames the quantum computing story through a single number: two-qubit gate accuracy. "When I entered quantum computing, which would have been in the late 1990s, it would have been like a major advance to just make a single two-qubit gate that was like 50% accurate," he explains. "That's nowhere near what you need for error correction to become a net win."

The theoretical threshold for error correction to work—the accuracy level at which adding more physical qubits actually helps rather than hurts—was estimated at 99.9999%. Six nines. The chasm between 50% and 99.9999% seemed nearly unbridgeable.

But the hardware kept improving. By Google's quantum supremacy demonstration in 2019, two-qubit gates had reached 99.5% accuracy. And within the past year, Aaronson notes, "the new state of the art is 99.9% accuracy." Meanwhile, theoretical advances in error correction have lowered the threshold requirement.

"And so now, the two numbers, at least on paper, have just about met each other," he says. "For the first time, we are sort of at the fault-tolerance threshold."

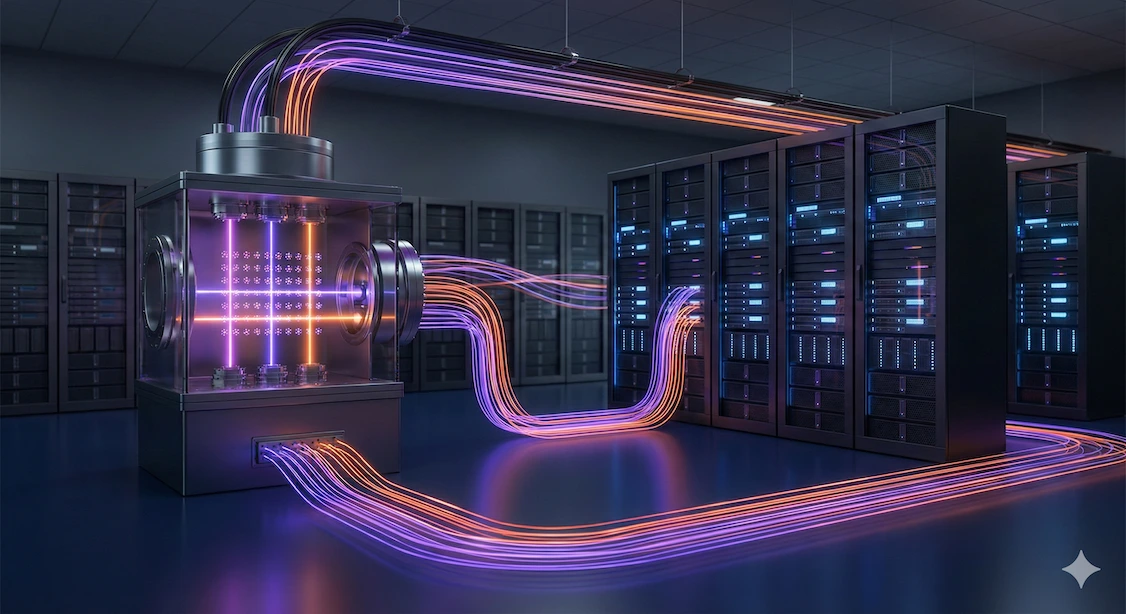

Three Horses in the Race

When asked about which hardware modality will ultimately win, Aaronson offers an assessment: there may not be a single winner, at least not yet.

"It's a surprise to me that there isn't [one clear winner], that we still have these several radically different hardware approaches that just seem to have complementary strengths and weaknesses."

He identifies the three leading approaches: neutral atoms, superconducting qubits, and trapped ions.

Neutral atoms—the approach QuEra is leading—are "winning right now in how many qubits they can do experiments with," Aaronson observes. While he notes that "the accuracy of the two-qubit gates is a little bit below like what the trapped ion can do," neutral atoms offer a distinct path to scale.

Superconducting qubits—the technology behind Google and IBM's systems—are fast, executing billions of operations per second. But they're fixed in place. "Each qubit can only interact directly with its nearest neighbors on the chip," Aaronson explains. Moving information requires cascades of swap operations, each accumulating error.

Trapped ions are slower but flexible. "What companies […] have now demonstrated is that they can just, in a fully programmable way, they can pick the ions up and move them around to wherever they want them to be."

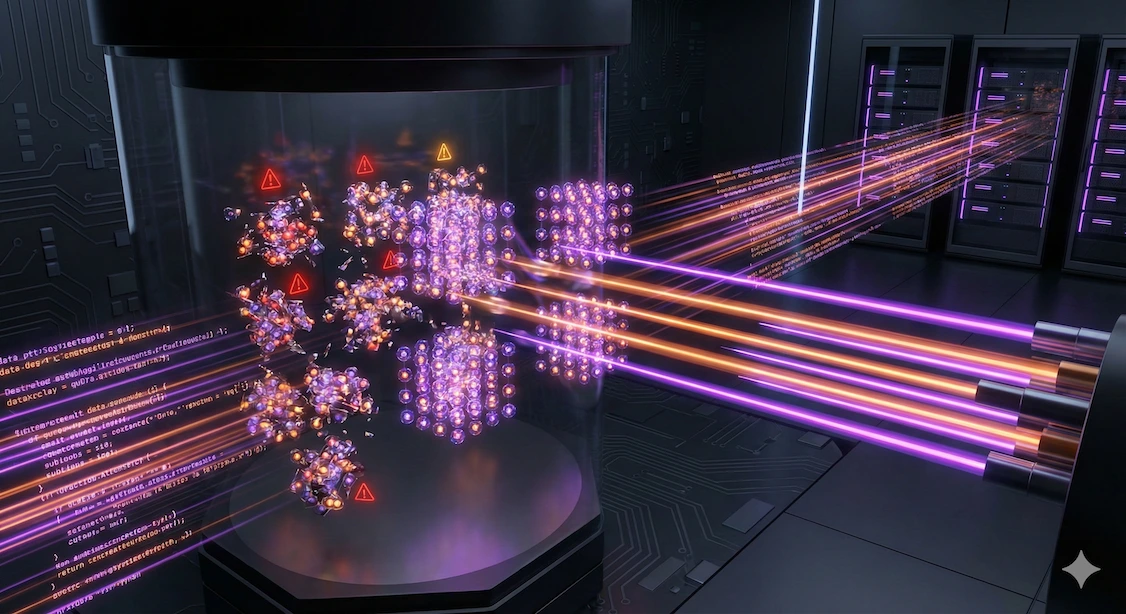

Quantum Error Correction Is Actually Working

The most significant development, in Aaronson's view, isn't any single hardware metric. It's that quantum error correction—the technology that should "ultimately enable this to scale to thousands of qubits, millions of operations"—has started to actually work in the lab.

"The basic theory of quantum error correction we have known since 1995 or so. So again, this theory was worked out 30 years ago. But only within the last year or two have we seen error correction really start to work in the lab in a way consistent with the theory."

He points to specific demonstrations: Google showing an error-corrected qubit whose lifetime increases with more physical qubits, and work from QuEra and others involving error-corrected qubits.

For enterprises evaluating quantum computing, this is the signal that matters. Error correction isn't a theoretical promise anymore. It's demonstrable.

A Credible Timeline

Aaronson is careful about predictions. "If I could reliably estimate the number of years that it would take, then I wouldn't be a professor. I would be an investor."

But he's willing to stake out a position: "I do take seriously the possibility that we will have sort of large fault-tolerant devices within the next few years, by maybe, I couldn't say, 2028, 2029, something like that."

This is notable precisely because of what Aaronson doesn't say. He doesn't claim fault-tolerant quantum computing is imminent. He doesn't promise revolution next quarter. Given what he's seen in the past year, fault-tolerant systems by the end of the decade are a serious possibility.

"If you just look at what has happened over the last year, I think it has met or exceeded, certainly what my expectations were."

The Commercial Implications

For enterprises considering quantum computing investments, Aaronson's assessment suggests several implications.

First, the technology has crossed an important threshold. Error correction working in the lab—not just in theory—means the path to useful fault-tolerant systems is now an engineering challenge rather than a physics question. "What remains is merely this unbelievably complicated engineering problem," Aaronson notes with characteristic understatement.

Additionally, the timeline is tightening. Organizations that begin building quantum expertise and identifying high-value use cases now will be better positioned when fault-tolerant systems arrive. Those waiting for certainty may find themselves years behind.

A Theorist's Warning

Aaronson closes with characteristic directness about separating signal from noise in quantum computing claims. "When someone is, when you encounter like a salesman, or a sort of, who has some slick pitch about what all the things that quantum computing will revolutionize," he advises asking basic questions: Does this actually beat what a classical computer could do? What quantum speedup are you talking about?

"Quantum computing is not just this magic pixie dust that speeds up everything. If you want to speed up, it should be connected to one of the quantum algorithms that we actually know."

His prescription for evaluating claims: "If people knew enough to just ask those kinds of questions and insist on answers, that would cut out like 90% of the BS that there is in this field."

That's advice worth heeding. The technology is real. The progress is genuine. The timeline is tightening. The task now is distinguishing substance from hype—and building the capabilities to capitalize when fault-tolerant systems arrive.

.webp)

-compressed.jpg)